Chronic absenteeism is not a new phenomenon, but a sharp increase in absences after the COVID-19 pandemic has created a serious problem with dire consequences for students, teachers, schools, and communities.

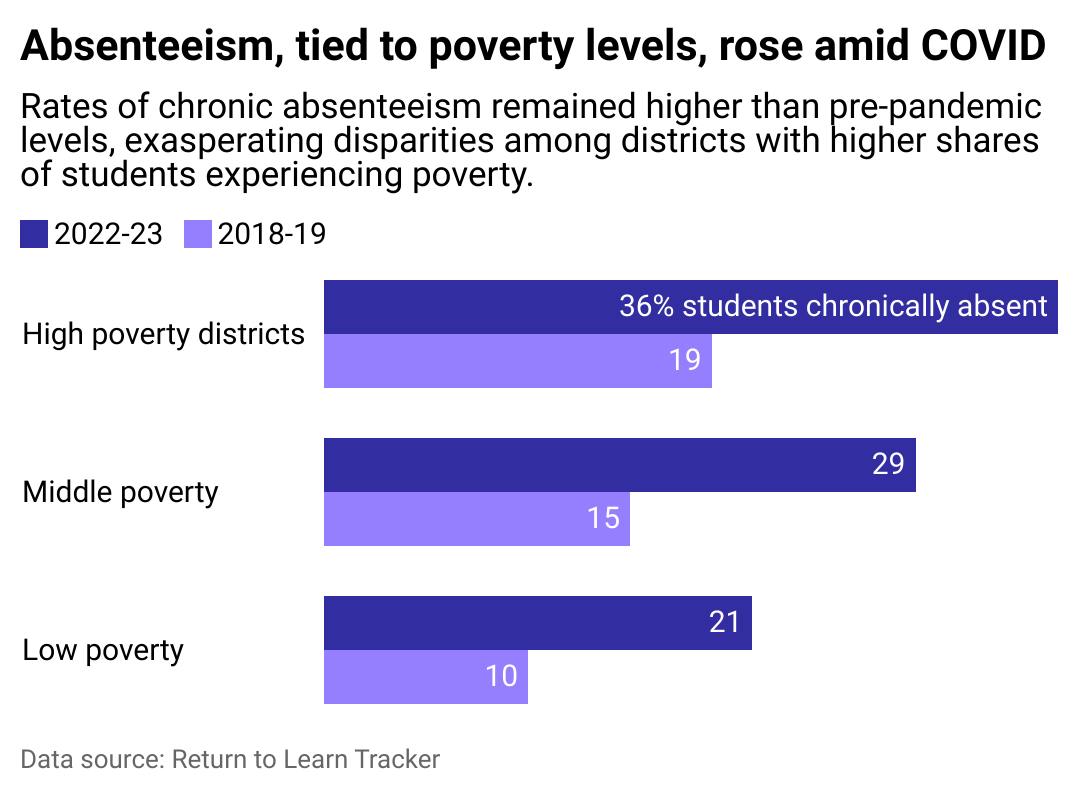

Study.com used data from Return to Learn Tracker to explore rates of chronic absenteeism, especially as it connects to economic circumstances.

Chronic absenteeism occurs when a student misses 10% or more of school days for excused and unexcused absences, as well as suspensions. While every state is different, most require about 180 days of schooling a year, meaning that a chronically absent student misses over three weeks of classes. Students experiencing absenteeism are at risk of falling behind academically or even dropping out, which could lead to less earning potential as adults.

Colonial Puritans in Massachusetts championed the idea of mandatory schooling, but once the Industrial Revolution hit the U.S. in the 18th century, children, lured by paying factory jobs, started leaving school.

An 1873 state law aimed to curb the trend by mandating 20 weeks of attendance per year for children 8 to 12. Truant officers patrolled the streets to find offenders, issuing fines as high as $5 a week (around $130 in 2024 dollars). Kids who skipped school could also find themselves in juvenile court. Under the law, about 100,000 Texas children go to court yearly to face truancy charges, and some go to jail.

Over the years, the age range and amount of schooling increased, and the concept of mandatory schooling spread across the country. As mandatory schooling became the norm, compliance rates also increased; in 1890, only 6% of teens went to high school, but by 1930, that number grew to about 50%, ProPublica reports. By 1950, school attendance was a given, and those who quit were labeled dropouts.

Today every state's laws determine the ages children must attend school, and many have changed their enforcement approach. Texas overturned its criminal law in 2015, finding that the threat of fines and prisons wasn't getting kids to school—particularly those from economically disadvantaged families and those facing other obstacles to attendance.

Some states now put the responsibility on parents and target them with fines and even jail time. In 2023, one Missouri mother received a 15-day jail sentence because her child missed 14 days within five months. These efforts caused a 53% drop in truancy cases from 2012 to 2021, according to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

However, the pandemic caused a massive shift in the momentum of school attendance. Pre-pandemic, 8 million students were chronically absent, according to Attendance Works' analysis of federal data. When schools shut down, children got accustomed to logging on to class (or not) from home. With limited structure, many students began skipping class. Once schools reopened, some parents found it difficult to rebuild the routine of school attendance, and children struggled with the demands of in-person learning and engaging in constructive face-to-face interactions with peers. In the 2021-22 school year, chronic absenteeism rates soared nearly 84% to 14.7 million.

Typically, high schools face the largest rate of absenteeism, but post-pandemic, absences in elementary and middle schools spiked. In the 2017-18 school year, in 7% of elementary schools and 8% of middle schools, almost 1 in 3 students were chronically absent. In the 2021-22 school year, the rate jumped to 38% and 40%, respectively. High schools also saw a jump, from 31% to 56%, per Attendance Works.

Some school districts are trying to tackle the problem of chronic absenteeism from an economic viewpoint. In the Detroit area, some schools work with companies that perform home visits, dispatching case workers to uncover issues parents face in getting their children to school and finding solutions to get children back into classrooms.

Children from economically disadvantaged homes often have to overcome myriad issues just to get to school: Their family may not have access to working laundry machines; it may be too dangerous to walk to school; they may have a treatable illness but don't have access to medicine; or they may not have stable transportation to get to school.

Some states, like Connecticut, New Mexico, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts, have developed campaigns addressing the importance of good attendance habits and staying in school. Connecticut and Virginia have created programs to foster partnerships between families and educators, establishing the necessity of school attendance clearly and providing extra learning tools to help students catch up on literacy post-pandemic.

States hope that by better engaging children and addressing their underlying needs, youths will attend school through high school graduation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics found that in 2022, workers who graduated from high school and didn't go on to college earned a median of $853 a week, 25% higher than those who didn't complete high school. This disparity demonstrates that a diploma could be the key to a better economic future for many children.

Data reporting by Emma Rubin. Story editing by Shannon Luders-Manuel. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Study.com and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.